We're heading back into the world of The Witcher. It's official. But instead of following Geralt and the School of the Wolf, CD Projekt Red has chosen to jump into a whole new saga with the fan-made upstart, School of the Lynx, and an as-yet-unnamed new protagonist, all dressed up in Unreal Engine 5. It's a departure no-one could have predicted – but there's tangible excitement about the idea amongst Witcher fans of all flavours. As we prepare to leave the long-suffering, grizzled Geralt behind, though, it's tempting to look back on where his story began.

The Witcher’s world is built on the creaking backs of characters who look much younger than they are. Mutants and sorceresses who could pass for 40 or 20, respectively, but have seen more kings’ faces than a merchant with a bag full of coins. Don’t be fooled by the smooth skin. Their youth is a facade that rarely holds up in conversation, the rigid thinking and displaced perspective of old age soon showing through.

Were CD Projekt RED to remake The Witcher – its first ever RPG – the result would be much the same. No matter how shiny it might look on the outside, this is a game that could never be mistaken for a modern product, or accepted as one, once it opens its mouth.

It’s not that the studio’s debut was a bad Witcher game, or a poorly-written one. So many of CDPR’s high level decisions were sound: to set the story after the books, rather than repeating old events; to bring back Geralt as protagonist, despite the ‘00s fashion for character creation; to locate the action in the city of Vizima, where the consequences of Geralt’s past actions could play out. It’s these decisions that make the games such great companion pieces even now – existing comfortably alongside the novels and the Netflix adaptation, each part further enriching the others.

It’s clear too that, from the beginning, CDPR was the right developer to tackle Wiedźmin, as the Witcher series had been known until that point. Watch behind-the-scenes interviews – particularly those aimed at the Polish audience – and you can sense the team’s awe for Andrzej Sapkowski’s work. Their commitment to his “inherent” humour, emotional truth, and rejection of easy answers in his stories.

“Those books are about modern people,” said chief designer Michał Madej. “You can easily understand their motivations. They don’t want to save the world by dropping a ring into a volcano. They just want to have fun, to gain power, to earn money, to drink. They are real, the problems are real, the decisions in the game’s world are real.” It’s a guiding statement that ultimately led CDPR to The Wild Hunt and mass cultural resonance.

Yet the precise, purposeful plotting that would define later games is absent in The Witcher 1. The dialogue itself is perfectly good – taken individually, practically every line is illuminating, funny, or at the very least functional. But the dense tree of quest logic they hang from is as gnarled and twisted as the one that sits on the Whispering Hillock.

This structural confusion has a muddling effect. New information has a habit of materialising in Geralt’s mouth, as if he’s been carrying out his own investigations while the player is asleep. Other conversations, meanwhile, can be bafflingly empty – bare scaffolding waiting for events to occur elsewhere in the game before they can be dressed with meaning.

There’s nothing wrong with safety-netting the player with a repeating interaction they can come back to once there’s more to say. In fact, it’s a fundamental apect of RPG design – a necessity that makes the conversation wheel go round – and even Bioware was guilty of implementing the basics a little clumsily back then. In The Witcher 1, however, that clumsiness is exacerbated by inexperience and budgetary constraints.

It all comes to a head in Chapter Two, which CDPR intended to be a detective story replete with a gumshoe, the private investigator Raymond, in a high-collared trench coat. It’s Raymond who’s supposed to anchor your search for Salamandra, a criminal organisation which has attacked Kaer Morhen and stolen witcher secrets from its lab. But as lead narrative designer Artur Ganszyniec told TheGamer last year, the second act’s dialogue was recorded before the mystery started to make any sense.

Today, CDPR would simply solve the problem with money, re-recording the offending lines. But for the fledgling studio, that wasn’t an option. Instead, Ganszyniec spent three days rewriting journal entries in an attempt to reconstruct the story around the recordings, and “learned a lot about how not to design investigations”.

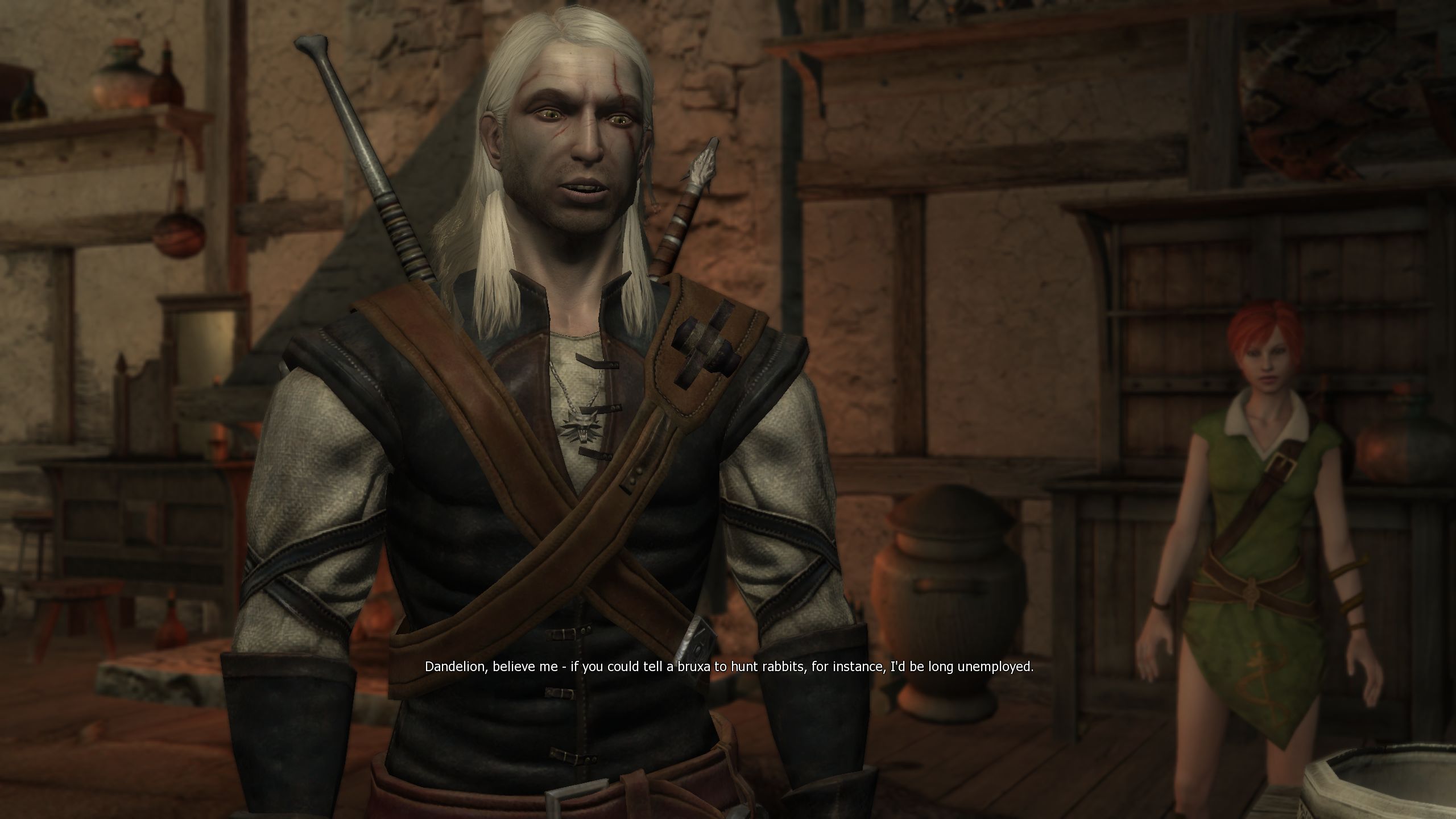

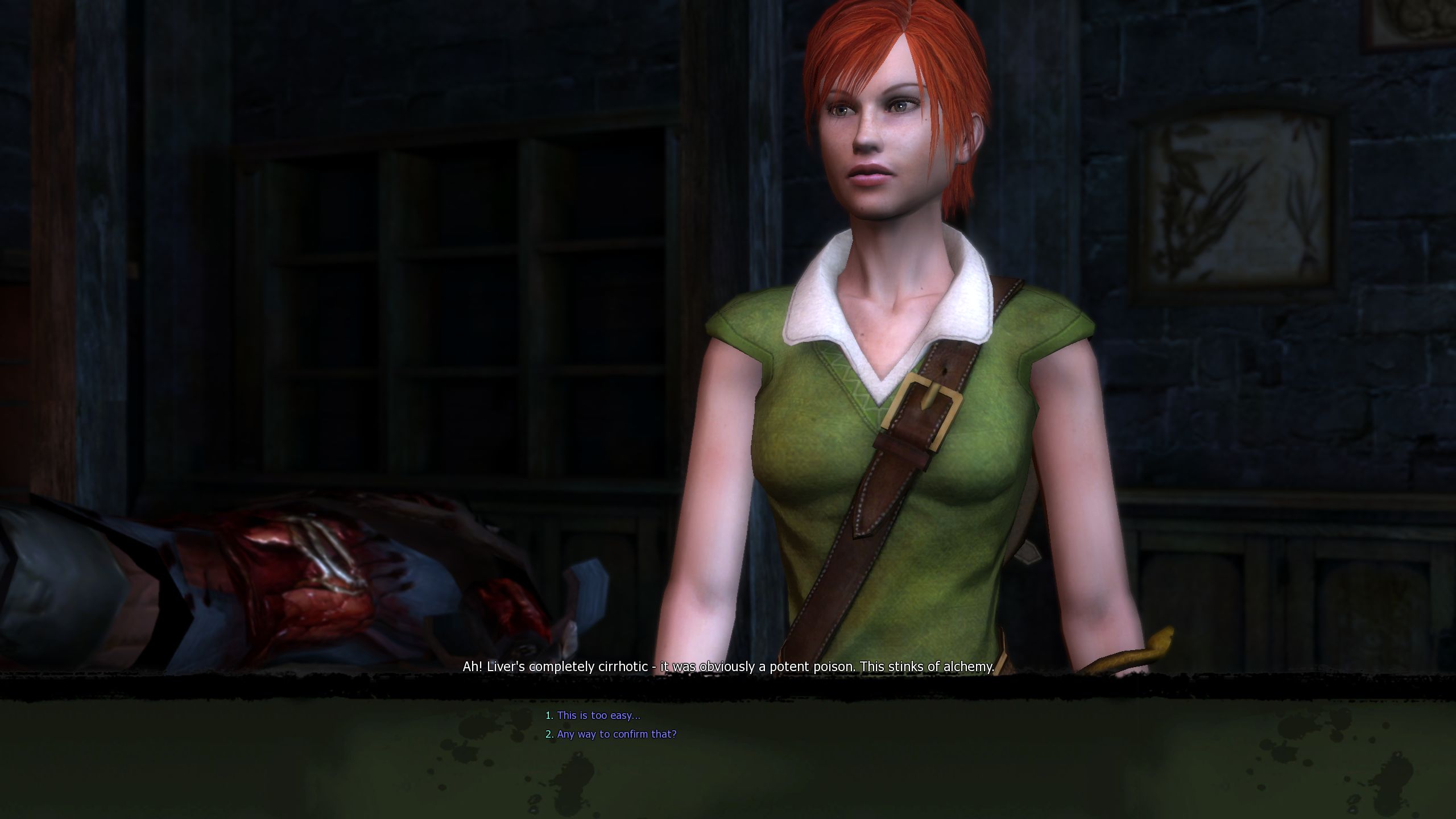

As you can imagine, that solution leaves The Witcher 1’s main quest muddy at best, and unnavigable at worst. In the most egregious instance, I cottoned onto a crucial character deception – but found the game gave me no option to call it out. Only by digging into a wiki did I learn that I’d need to load an earlier save to take the path I wanted to; I’d picked the wrong fork in an innocuous dialogue choice during an autopsy. If you can detect the cataclysmic difference between the two lines below, you’re a better sleuth than I:

Moments like these are exactly the wrong sort of ambiguity, in a series that’s otherwise celebrated for its grey areas.

Do I wish that CDPR had reined in its narrative ambition, and so put out a less garbled game? Not really. The same ambition that makes The Witcher 1 such a fuzzy story experience eventually led CDPR to master the art of branching narrative in the sequels.

Yet these early errors close off any easy routes towards a remake. Sure, you could replace The Witcher 1’s pirouetting, mouse-and-keyboard combat style with a more modern dodge ‘n’ block system, in line with The Witcher 3. You might touch up the dialogue here and there, as Hangar 13 did with Mafia: Definitive Edition – deepening characters who were only thinly sketched the first time around. But in both cases you’d be dancing, Geralt-like, around what’s really needed: a full-scale rewrite in order to bring the game’s narrative structure up to scratch. Suddenly, the project starts to sound less Mafia: Definitive Edition, more Final Fantasy VII Remake. And at that point, you have to question the value of the whole enterprise.

It’s a strange and sad conclusion to come to. The Witcher 1 was a rightly-acclaimed computer RPG which, due to various production problems, never reached consoles – and therefore appears to have huge untapped potential. Given the striga-like appetite for all things Witcher, it would seem like a no-brainer for CDPR to resurrect it. Yet when the rework required is so fundamental and extensive, the studio might just be better off building a Witcher 4 instead.

This story was originally published under the headline: Please give us The Witcher 4 over a half-baked remake of the original.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7t7ORbW5nm5%2BifLG4xJqqnmWXnsOmedSsZK2glWLEqsDCoZyrZWRivLex0WaYZqCRobNursCknJ1lopq6orfEZqafZaSdsm7DyK2aoZ2iYn4%3D